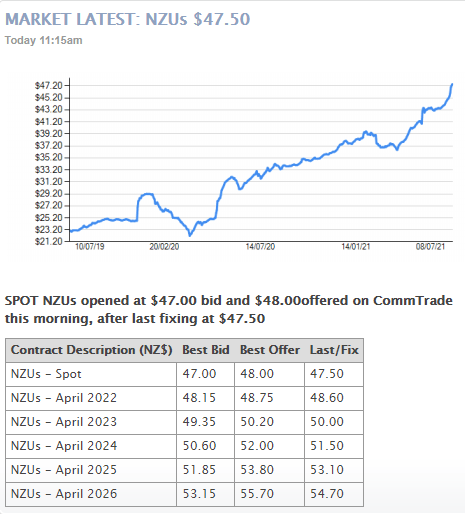

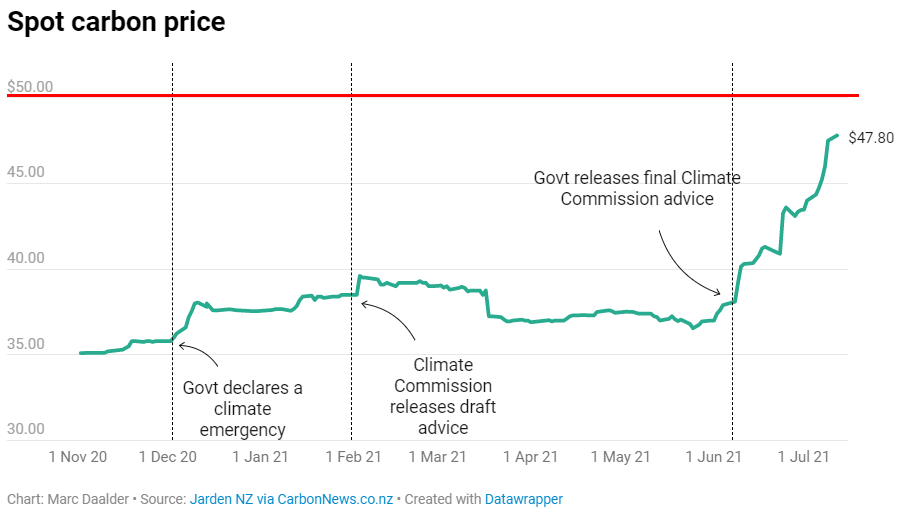

With prices turning vertical on the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) over the last two months, the government finds itself exposed to fiscal and reputation risks.

These risks do not come from the price increases per se, but from the way the price cap mechanism introduced to the ETS this year.

The price of carbon on the ETS now sits at $48, just $2 below the $50 price cap.

The cap could be breached at either of the next two auctions on 1 September and 1 December.

Source: Newsroom/Marc Daalder

According to Newsroom, Climate Change Minister James Shaw has ruled out raising the price cap.

The ETS has had a price cap for years. Before changes last year, the price cap was very simple.

The government gave effect to the cap with a standing offer to sell an unlimited number of emissions units at the fixed price.

For years, the price cap was $25. The government would sell any number of units to anyone willing to pay $25 for each unit.

Nobody was going to pay (much) above $25 for emissions units if they could buy from the government instead. Thus the government’s standing offer capped prices.

But price certainty came at the cost of quantity uncertainty. The problem with selling unlimited emissions units to enforce the price cap is that it left emissions uncapped. Every emissions unit sold to enforce the price cap meant extra emissions.

The ETS was a cap-and-trade system without a cap.

Changes to the ETS in 2020 fixed that problem. The changes retained a price cap, but put a limit on how many emissions units could be sold to defend the cap. This year that number is 7 million emissions units. Those units are held in a ringfenced pool called the Cost Containment Reserve, or CCR.

The advantage of this approach is that it gives the ETS a hard quantity cap.

But certainty on quantity makes the price cap soft. Once the units in the CCR are exhausted, there are no more units to defend the price cap. The price cap is then breached. Prices will be free to rise above the cap based on supply and demand until the reserve is refilled next year.

Rising ETS prices means there is a real possibility the new price cap is about to be breached in its first year of operation.

For anyone who is concerned about greenhouse gas emissions, the higher ETS price is unambiguously good news.

A rising carbon price will drive greener consumption by households and businesses. The ETS covers almost everything in the economy, the main exception being livestock. And the fact that the ETS price has risen so steeply in the last 12 months without much or any complaint is points in favour of its political viability.

But reaching and possibly breaching the new price cap so soon after its introduction will bring problems.

The first is the risk of a speculative attack on the price cap. If the market believes the fair price for units, even after the release of the seven million units from the CCR, sits north of $50, then there will be what amounts to a run on the bank.

A run would play out like this. The government sells its seven million reserve units for $50 a piece. The CCR is exhausted and prices rise above $50. Speculators then sell the units, cashing in on the difference between the market price and the $50 they paid for the units. Taxpayers take a hit. Treasury writes off the loss. Nobody comes out looking good.

A second set of risks arises from a rule introduced in last years reforms which says the government must ‘back’ some of the units it sells to defend the price cap.

Normally, selling extra emissions units means higher emissions. The idea of ‘backing’ units is to sanitise units sold from the reserve so that they do not raise emissions. In effect, the ‘backing’ rule says the government must offset the extra emissions of reserve units.

In principle, this is an elegant mechanism that rightly gives priority to credibility of the emissions cap in the ETS.

But it takes systems and processes to do the job properly. It is not clear the government has had time to put the systems in place to properly offset emissions.

The key issue here is credibility. Offsetting emissions is not particularly difficult in itself. Trees capture and store known amounts of carbon per hectare. It is possible to buy and shred emissions units from any of the ~27 other ETSs around the world. Or to partner with organisations that specialise in offsets. And so on.

But the offsets have to credible in the eyes of the government’s supporters. Many environmentalists do not like the idea of writing cheques to cover our carbon footprint. They worry about a repeat of the Ukrainian credits scandal from the first half of the 2010s. They do not like planting trees to offset gross emissions.

At stake is the ETS itself. The offsets are defending the ETS cap. That is the whole ballgame. If the offsets are not credible, then the credibility of the cap and the ETS itself could come into question.

So what are the government’s options and what will it take to manage the credibility question?

The government could plant trees on Crown land. Those trees must stay outside the ETS permanently so that the carbon captured and stored by the trees does not lead to new emissions units being issued. Provided that is the case, the trees will genuinely offset the extra emissions from the ETS brought about by the extra units from the reserve.

That seems simple enough. But there must be systems in place to keep track of what carbon capture is additional and what is not. The trees must remain outside the ETS to be a genuine offset. If they were ever to come into the ETS any time in the next 30 years, there would need to be accounting in place to trigger additional offsetting elsewhere. Then there is the question of what happens after the trees are harvested – whether they are replanted or not. The government needs processes in place for any promise it has offset emissions to be believed.

Alternatively, the government could look offshore. The European ETS is the world’s largest carbon market. The government could buy and then shred EU emissions units. That would credibly lower global emissions, meeting the backing rule.

The problem is emissions units from the EU are trading for nearly double the cost of units here, about NZ$92. Using EU units to back units here could result in a loss of more than $60 million per year at current prices. That loss could raise credibility problems of its own.

The government could consider more affordable emissions units from ETSs in other countries.

But that would raise the question of how the government provides assurance that the emissions units from those ETSs are real, that the government in the source country will not simply print more units in the future making the units we bought worthless.

These are hard problems that will take time to solve. Even if the government goes with domestic solutions, it does not seem to have any way to demonstrate the emissions reductions are real and permanent.

There is no discredit to the government for the awkward position it finds itself in. Few if any could have foreseen the steep increases in the ETS price. We have hit the ETS price cap far sooner than anybody probably thought.

But rules are rules and the government may have to find a solution to the backing problem quickly.

Perhaps the simplest solution is to get rid of the price cap. It is not necessary, and in any case it is a chimera: little more than a stop gap measure. If the fair price for emissions units is above the cap, the market will have no trouble blasting through the price cap.

The ETS has well-established spot and forward markets that give businesses and their customers ways to manage their exposure to fluctuating carbon prices – exactly what the price cap is meant to do.

The domestic ETS price has to be managed – no two ways about that – while maintaining a credible track to our emissions targets. The way to do that is use international offsets as a relief valve, accessing them as required to stay on track to our targets while keeping the domestic carbon price aligned with our trading partners (or whatever principle the government of the day decides appropriate).

Using international offsets in this way requires us to be organised about that access. We should be seeing an effort to put in place the systems and checks and balances that gives the current and future governments the option to go offshore when necessary, with the assurance, of course, that every international unit we trade or project we fund is authentic.

The current strategy combines a hard domestic emissions cap with international isolation. This has predictably led to price volatility in the ETS. We need to be smarter than this.

Going offshore does not mean doing nothing here. It means being prepared to open the door to offshore when necessary to stabilise prices here. Going offshore to cover 100% of our emissions reductions is too much. But 0% is too little.